I have one of those kids who wants to know how everything in the entire world works. He needs to investigate every single thing to death. Thank goodness we have Mighty Machines and Bill Nye streaming on Netflix. How do airplanes fly, Mama? What makes a semi-truck go? How do binoculars magnify? Where does rice come from?

That last one made me pause.

Society's come a long way, but even when I taught 3rd grade a decade ago, the vast majority of kids in my classes couldn't explain how bread or milk wound up in their kitchen. I grew up next to a farmer who had an incredible impact on my life, and it was so empowering to crouch down with him and pull food from the soil. To me, that's grasping the very foundation of life. The building blocks of health. Families today are too busy or don't have the space to actually plant and pick their own food, but I still feel strongly that they should have access to products with transparent ingredients and processing so they can choose what works for their own body.

The cornerstone of that choice, to me, lies in education. I think it's crucial that people educate themselves about the many facets involved in food, where it comes fom and how it comes together. So I've hauled my kids around to more farms than any of us could possibly count, and I said “yes!” enthusiastically when Kellogg's invited me to one of their local family farm suppliers.

Which is how I found myself standing in the middle of a farm that supplies rice for Kellogg's.

“Come, get on the combine,” the farmer beckoned over to me. I hesitated and explained that I've been on plenty of combines, and his time would probably be better spent moving us all on over to the factory. “You haven't been on a combine like this,” he pressed. And he was right. I would later learn that pieces of equipment like this used for farming rice start at $200K and go up from there. I climbed aboard that satellite-driven machine and we turned in a BIG circle. I watched in amazement as the tines spun before me, doing a massive loop that would separate rice stalks up from the ground and pull them underneath us into a processor, yanking the grains of rice into a giant bucket.

I fan-girled when he explained the delicate ecosystem here on one of the Kennedy family’s original farms that now produces 8-10,000 acres of rice each year. “It's a duck habitat in between growing season. The Duck Dynasty folks have a blind here, and we have some eagle residents and about 50 alligators in between growing seasons.” Gravity flow irrigation diverts water from the nearby river at about 18,000 gallons per minute into a sophisticated system of canals and irrigation to water the rice with exact precision. No water is wasted in the process; it's a fully-sustainable system encouraged by Kellogg's to increase productivity and quality through climate-smart agriculture practices.

There's even more to it than that, though. You can't plant rice every year back-to-back, so they often plant soy in between to help balance the soil. Rice takes 120 days to grow and is harvested from August through October. In the midst of all that, they have years where they let the land rest and adjust soil fertilization to get nitrogen levels right. It becomes even more complicated if they aim for organic rice. This farm has 2,040 acres dedicated to certified transitional rice for Kashi, which makes use of the rice grown between conventional and organic farming in a three-year period.

We drive the 8 miles from end-to-end on this particular farm, across town to the owner's home where he raised his four children – three of whom now work on the farm. His daughter, Meryl Kennedy, sits next to me at lunch as his wife, Anne Kennedy, serves us homemade gumbo. She proudly tells me that they own both the oldest rice mill and the newest rice mill in Louisiana.

It's quite a feat, given the fickle nature of the rice industry. Issues related to rice quality include moisture in the drying process, which can lead to chalky rice or stress cracks in the rice. And then, there are different types of rice, which require farmers to clean out the entire mill to ensure that there are no kernels of any other types of rice, no hulls or dust or anything. Kellogg's standards are high, seeking out the very best rice on the market. Buyers frequently request samples, but it's easier for the rice manufacturer to actually have the buyers send a sample of what they're looking for, and then the manufacturer can hone in on those very detailed rice qualities on their end.

I had no idea that rice was so specific. I only learned that there are different types of rice when I went to make homemade sushi a few years back and discovered that it requires short-grain Japanese rice as opposed to the traditionally longer-grained American or Basmati rice. Only certain types of rice have enough starch to properly stick to the seaweed paper.

Meryl goes on to tell me that white and brown rice are actually the same at their core: the only difference is that one has the bran layer removed beneath the hull and one does not. There's no bleaching or segmenting or deconstruction beyond that. The hulls and bran and dust usually get bought by pet feed. Nothing goes to waste!

One of the biggest challenges is actually finding qualified workers who want to drive combines around the rice fields. With intense water management required year-round, rice is one of the most labor-intensive crops in the world. It often leads to 80- or 90-hour weeks, and the younger generations are falling off because they're tired of dealing with droughts, hurricanes and other weather issues that impact the crop. The farming company actually has to buy rice insurance to offset the poor yield in bad years. Kellogg works with farmers and suppliers like the Kennedy family to practice climate-smart agriculture practice, which help to ensure farms are less susceptible to climate shocks, such as these.

I've interviewed dozens of farmers, and every one has expressed angst about the future of agriculture in general. The food industry overall suffers from slow response in the grocery store around pricing changes related to the cost of production. It's highly-competitive and people are very sensitive to price on the shelf, so either the consumer is upset or the labor is suffering…yet everyone is demanding higher wages. It needs to come from somewhere. In order to protect themselves from poor yields they may experience in bad years, the farming companies buy crop insurance – an added expense that has its benefits.

I shrug and nod and awkwardly shake my head all at once. Always one to problem-solve, I don't have any answer that's even remotely helpful. It's a problem that I feel as a mother, concerned about the growing gap between my children and their food sources.

We head to the mill to see what happens to the rice after it's harvested. I follow the grain from general cleaning machines that toss out anything that isn't sized right all the way to a scanner that takes a photo of every individual grain of rice to sort it. At the end of the line, a guy hands me a warm bag. It goes into my suitcase, through TSA and eventually lands on my kitchen table.

My son comes out to greet me in the morning. “How was your trip, Mama? What did you see?”

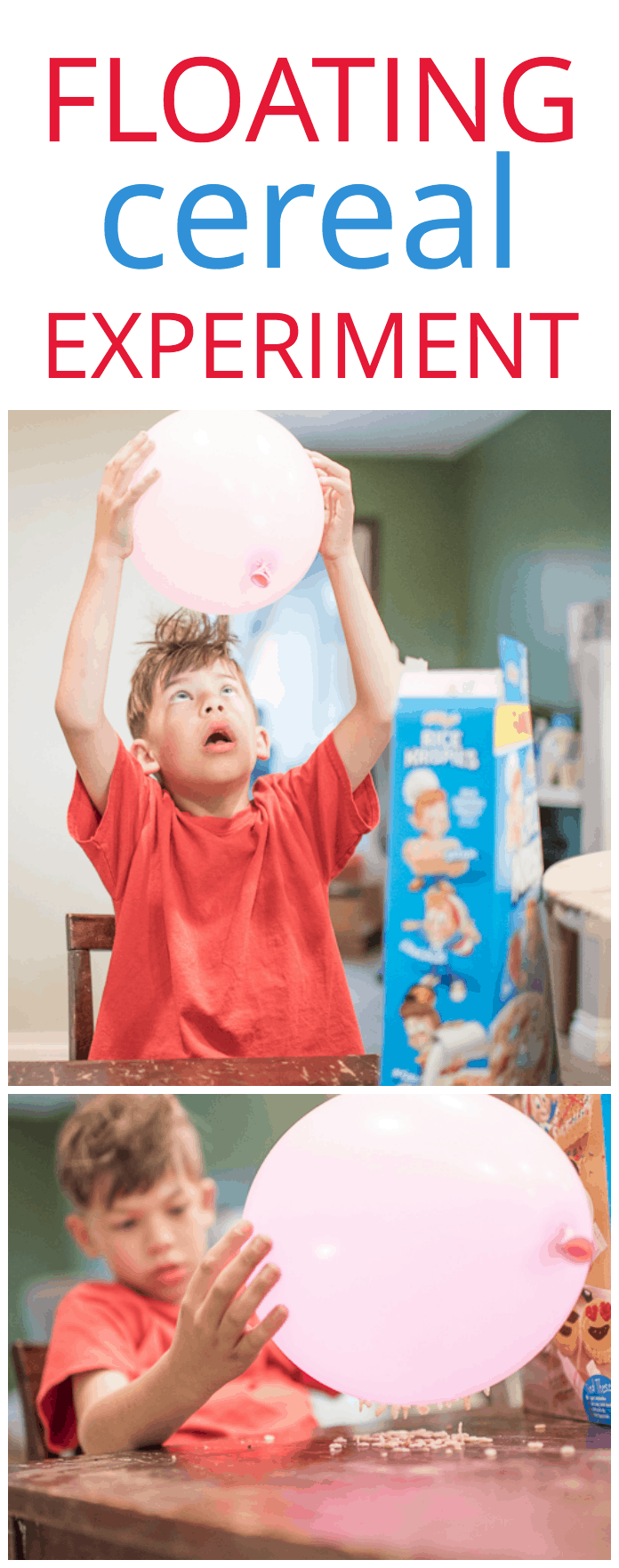

I pop open the top of his cereal box, as I always do, and linger over the bowl. I tell him about all the people and the machines and the company that goes into his breakfast. I explain how it comes together, and then I blow up a balloon, rub it on his head and make Rice Krispies hop up from the table. This happens due to the transfer of electrons giving the balloon a negative charge and pulling on the positively-charged Rice Krispies. I tell him that the whole world is made up of atoms, which are made up of electrons, which persistently transfer between objects that are either negatively or positively-charged. I illustrate the concept by showing how two magnets push against each other over by the fridge.

It dawns on me that this is a metaphor for the food industry itself. It's a give and take, with numerous forces taking part and vying for their interests.

For a minute I'm afraid that I might be overwhelming him, but he gets it. The thing is, when you can trace food to the source, it makes a ton of sense.

The only remaining question for me is how we keep encouraging that curiosity so our children continue the investigation. They need to continue tracing our food sources, seeking out education and advocating for transparency.

Our kitchen draws quiet, save for the snap-crackle-pop of his Rice Krispies, and I'm hit with a wave of nostalgia. If we can just keep that childhood wonder alive, maybe they'll get it. Maybe their hunger for knowledge will grow and we'll be able to keep improving our society's understanding of food.

“Hey mom,” he interjects into my thoughts, “why does my cereal pop like that?”

I smile and quickly reassure myself.

In this house, we're definitely keeping the conversation alive.